Interphase cell shape defines the mode, symmetry and outcome of mitosis:

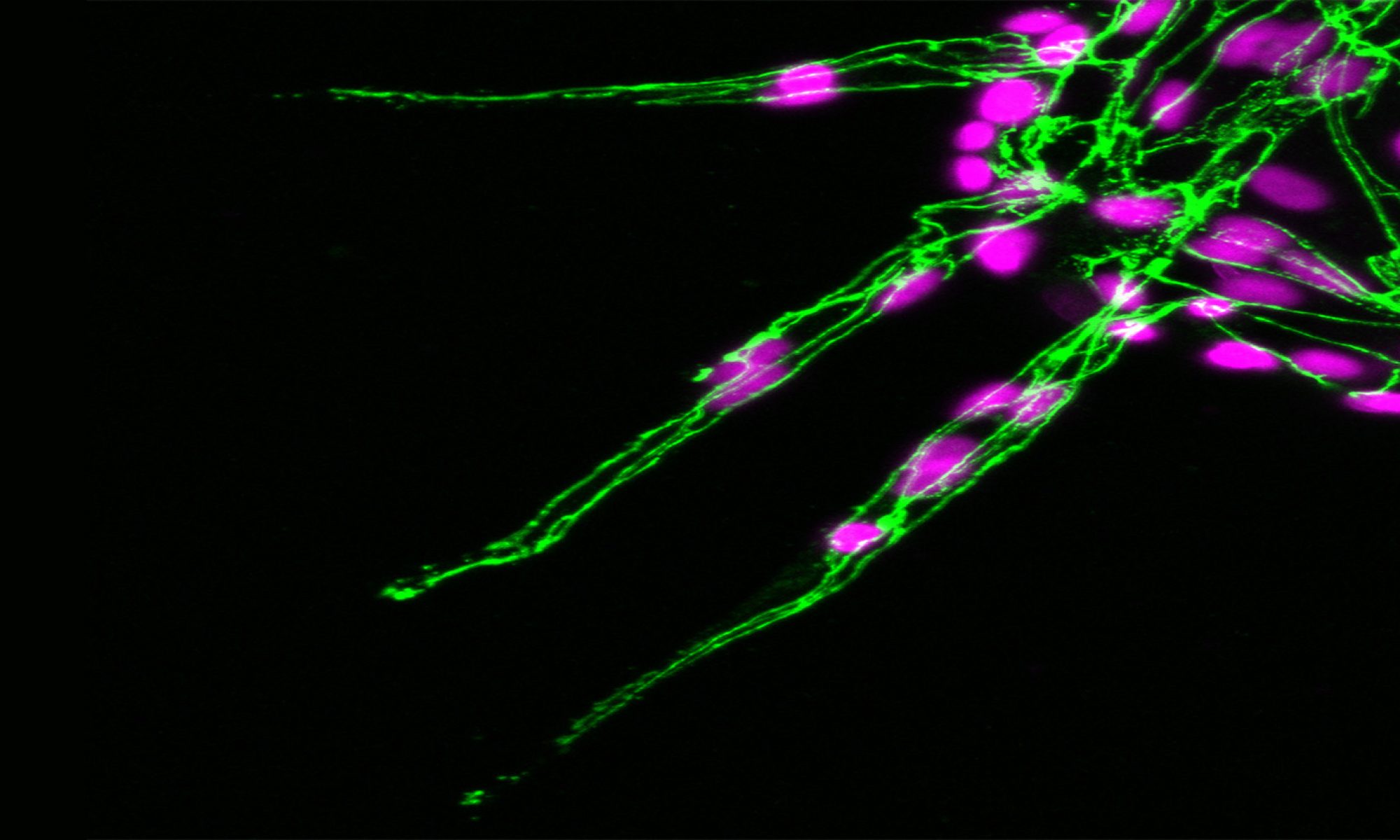

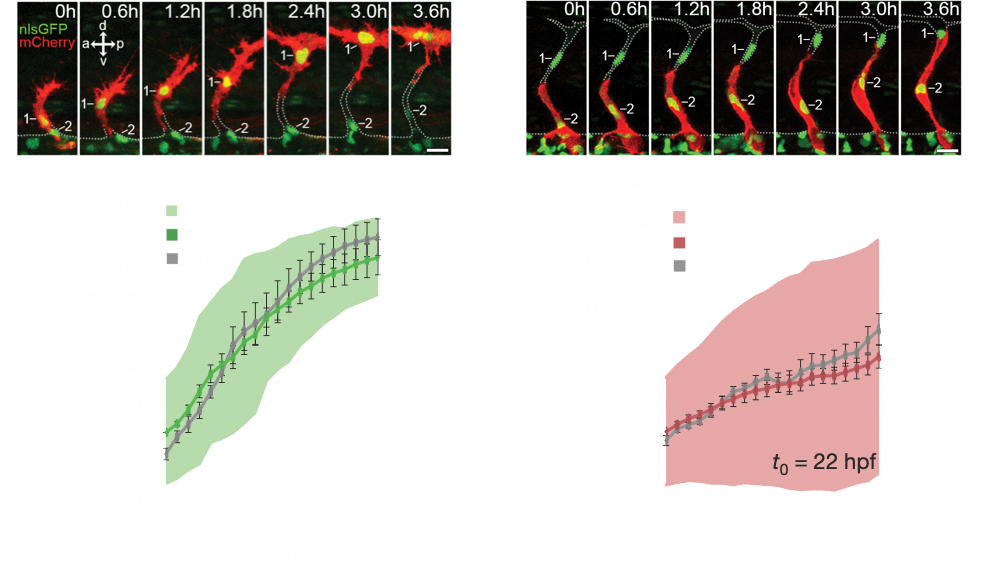

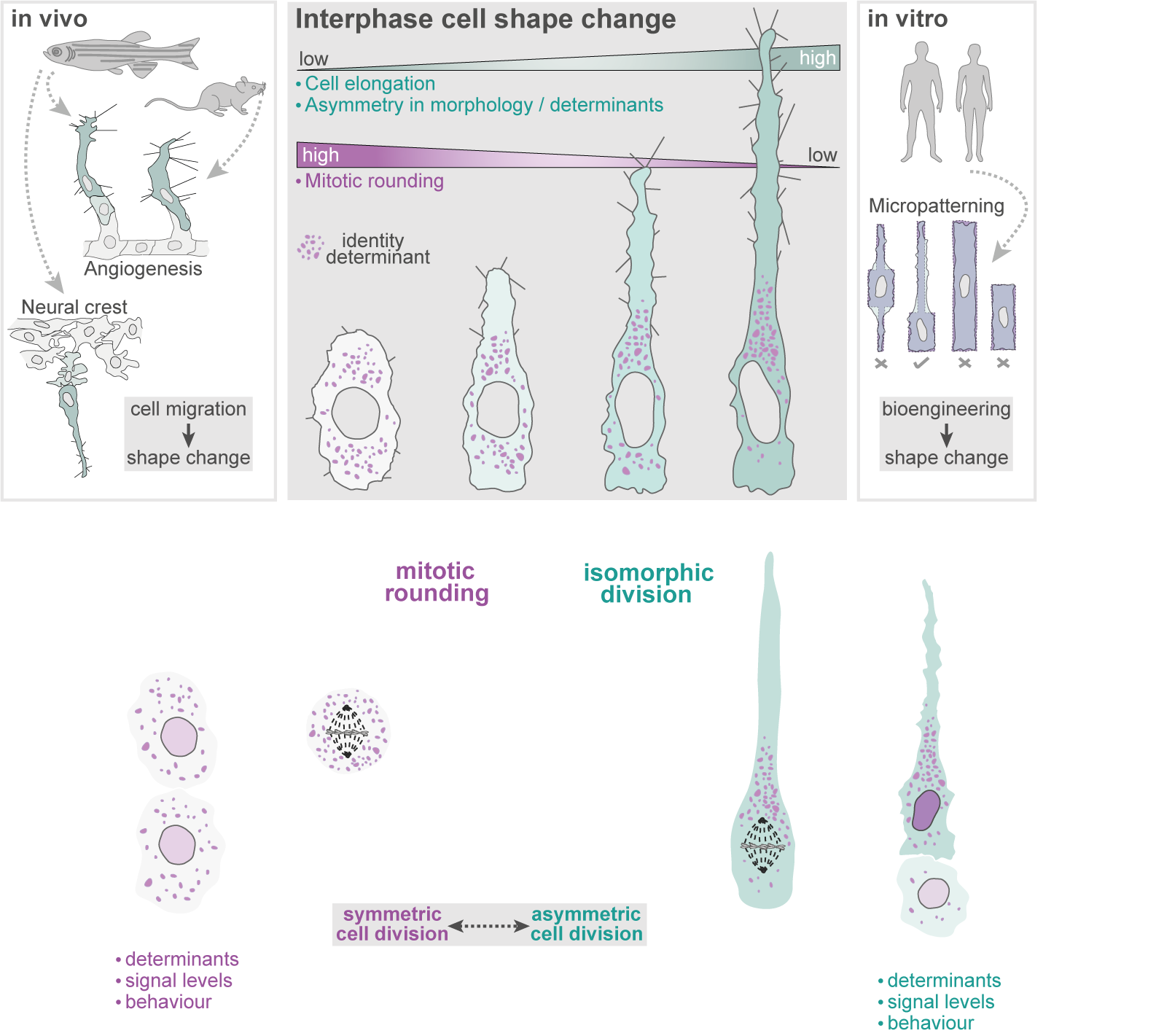

Angiogenesis is coordinated by the collective migration of specialised leading “tip” and trailing “stalk” endothelial cells. Exploiting in vivo live single-cell imaging in the zebrafish model, my lab previously demonstrated that these tip and stalk cells exhibit very distinct motile behaviours and cell shape dynamics (Fig.1). Moreover, using an interdisciplinary approach integrating in silico computational modelling studies, we demonstrated that dividing tip cells undergo asymmetric divisions (Costa et. al., 2016. Nat. Cell Biol.). These asymmetric divisions generate daughters of distinct size and tip-stalk identities, effectively self-generating the tip-stalk hierarchy that drives angiogenesis.

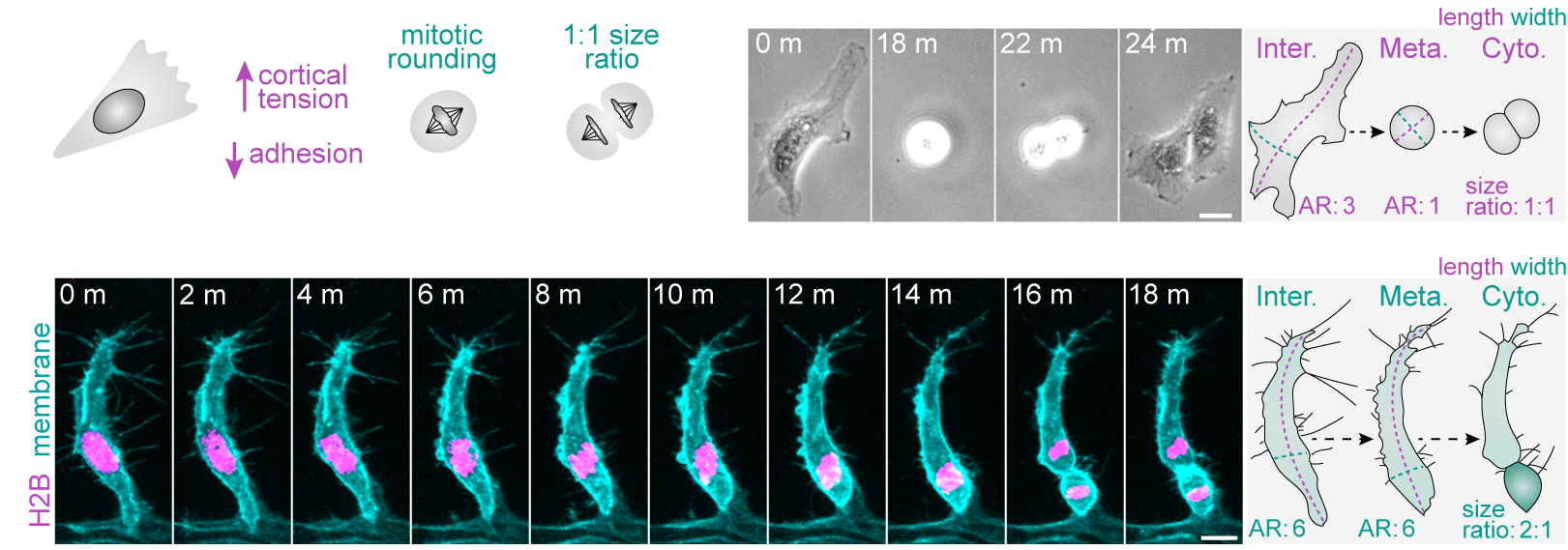

More recently, we demonstrated that a fundamental trigger for these asymmetric divisions is the shape of cells in interphase (Lovegrove et. al., 2025. Science). Most cells are thought to adopt a spherical geometry in division, a process termed mitotic rounding (Fig.2a). Indeed, endothelial cells in 2D culture exhibit classic mitotic rounding (Fig.2b). In contrast, we find that endothelial cells and other cell types in vivo can switch to a novel “isomorphic” mode of division, which uniquely preserves pre-mitotic morphology throughout mitosis (Fig.2c). We further identify that distinct shifts in interphase morphology act as conserved instructive cues triggering this switch to isomorphic division. Moreover, in isomorphic divisions, we find that maintenance of interphase cell morphology throughout mitosis ultimately enables cell shape to act as a geometric code defining mitotic symmetry, identity determinant partitioning, and daughter state (Fig.3). Thus, morphogenetic shape change both sculpts tissue form and generates the cellular heterogeneity driving tissue assembly.

mRNA localisation as a key determinant of cell shape remodelling and sensing:

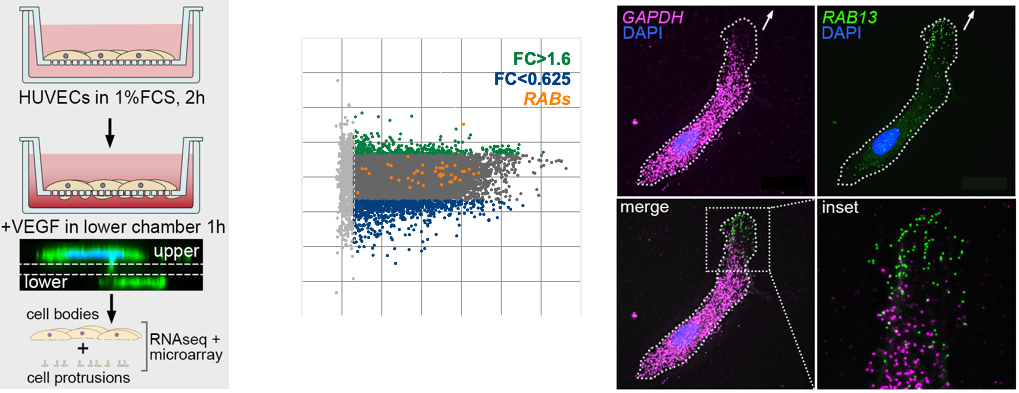

The polarised targeting of diverse mRNAs to the front of motile cells is a hallmark of cell migration, yet, precise functional roles for such targeting of mRNAs has long remained unknown. Likewise, their relevance to modulation of tissue dynamics in vivo is unclear. Using cell fractionation to isolate motile cell protrusions and RNAseq we previously defined distinct clusters of mRNAs that have unique spatial distributions in migrating endothelial cells, both in vitro and in vivo (Fig.4). Moreover, using single-molecule analysis, endogenous gene-edited mRNAs and zebrafish in vivo live-cell imaging, my lab previously demonstrated that such compartmentalisation RAB13 mRNA uniquely acts to promote local filopodia extension. Moreover, this local cell shape remodelling ultimately acts as a molecular compass that orients motile cell polarity and spatially direct tissue movement (Costa et. al., 2020. EMBO J – see movie below).

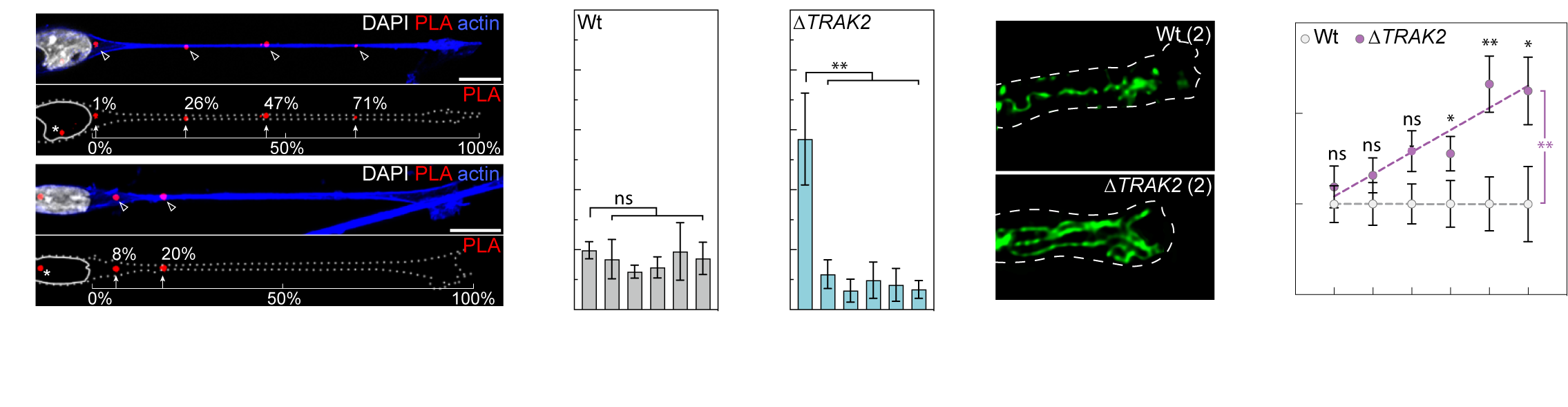

More recently, we’ve demonstrated that another one of these targeted mRNAs directs the cell-size-scaling of mitochondria distribution and function (Bradbury et. al., 2025. bioRxiv). We find that mRNA encoding TRAK2, a key determinant of mitochondria retrograde transport, is targeted to distal sites of cell protrusions in a cell-size-dependent manner. This cell-size-scaled mRNA polarisation in turn scales mitochondria distribution by defining the precise site of TRAK2-MIRO1 retrograde transport complex assembly (Fig.5a). As a result, excision of a 29bp 3’UTR motif that underpins this cell-size-scaling eradicates size-scaling of mitochondria positioning, triggering distal accumulation of mitochondria (Fig.5b) and progressive hypermotility as cells increase size. As such, we find an RNA-driven mechanistic basis for the cell-size-scaling of organelle distribution and function that is critical to homeostatic control of motile cell behaviour (Bradbury et. al., 2025. bioRxiv).